Shadows of Socialist Realism

Exhibition 'Shadows of Socialist Realism' in Memento Park Budapest

The mouth can have so many meanings. The word it speaks, whether good or bad, the language it expresses, a non-verbal action like a grimace, a bite, a spit, a wry smile of fear, or a sardonic laugh...

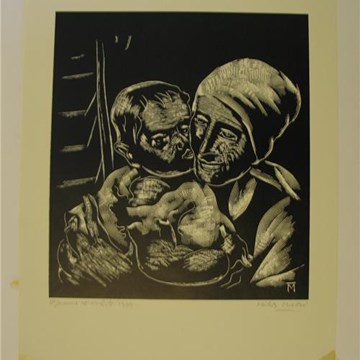

Anna Neizvestnova’s project Shadows of Socialist Realism is a gallery of portraits, or rather fragments of faces, smiles, and mouths of the participants in the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934 when Socialist Realism has proclaimed the main trend in aesthetics. Of the nearly 600 delegates, by the end of the 1930s, 220, more than a third, were repressed with varying degrees of brutality. The fates were woven into a socio-professional fabric — mutual assistance, competition, betrayal, censorship, and criticism, saving “in the desk” texts that could not be published.

The title “Shadows of Social Realism” was born from Anna’s general sense of this style — ideologically verified, unambiguous, devoid of doubt, like a burly tractor driver on a clear sunny day... what Anna is doing is exploring the shadowy, implicit side, and searching for the restless shadows and ghosts of the past.

Photography is tied to death as a medium, Susan Sontag said, and captures an elusive reality, preserving images of the faces of people long dead. It was this ghostliness that determined Anne’s choice of the original medium: the black and white documentary photography of the 1930s, which, incidentally, was already well into retouching during this period. The enlargement and translation of the images into the language of monochrome painting washes away the portrait's uniqueness and gives the works a fascinating and at the same time eerie effect, opening up the field of interpretation and imagination. The artist’s manner is so expressive that it verges on abstraction — coming closer the images lose their outlines, becoming a whirlwind of sweeping disturbing strokes.

The representational strategy chosen by Anna can be imagined as a double reversal: if photography is a light-recording of the concrete, then Anna focuses on shadow writing, increasing the distance between the object and its reception. Based on documentality, the author works with photographs of specific people, turning them into a distant reference, split beyond recognition, while reversing the fact itself, the story behind the visual text. The second reversion takes place at the level of meaning — the mouths of people who work professionally with language, for whom it is their profession that becomes the cause of persecution, and it turns out, “my language is my enemy.

A portrait is always a biography. In addition to images, an integral part of each work are explications with brief explanations, fragments of biographies, and facts of life of writers, which Anna, having processed a large array of historical materials, deemed worthy to show — images and texts enter into a complex ambiguous semantic fusion.

The biographical turn is a fashionable and relatively new approach in the humanities and art — an appeal to micro-histories, cases, life paths, and its special episodes, when through the personal destiny the canvas of time opens — the Soviet metanarrative.

Each biography is a grain of sand, stuck in the flow of time and caught in the archives, a testimony in which one can see a great era from a human perspective, understanding the motives, actions, and proposed circumstances — the gaping shadows of time.

Elizaveta Savolainen, culturologist

Exhibitions and events

The Most Cheerful Barrack

Permanent exhibitionThe Most Cheerful Barrack houses three permanent photo exhibitions and a movie show. The photos and descriptions sum up two outstanding events in Hungarian communist history: one is the 1956...

Secret Storage Room

Permanent exhibitionHidden in the basement of Stalin's Grandstand, visitors find a somber bunker with mass-produced Lenin and Stalin busts, including an exceptional piece of propaganda art.

Activities from this museum

We don't have anything to show you here.